Canine Cancers

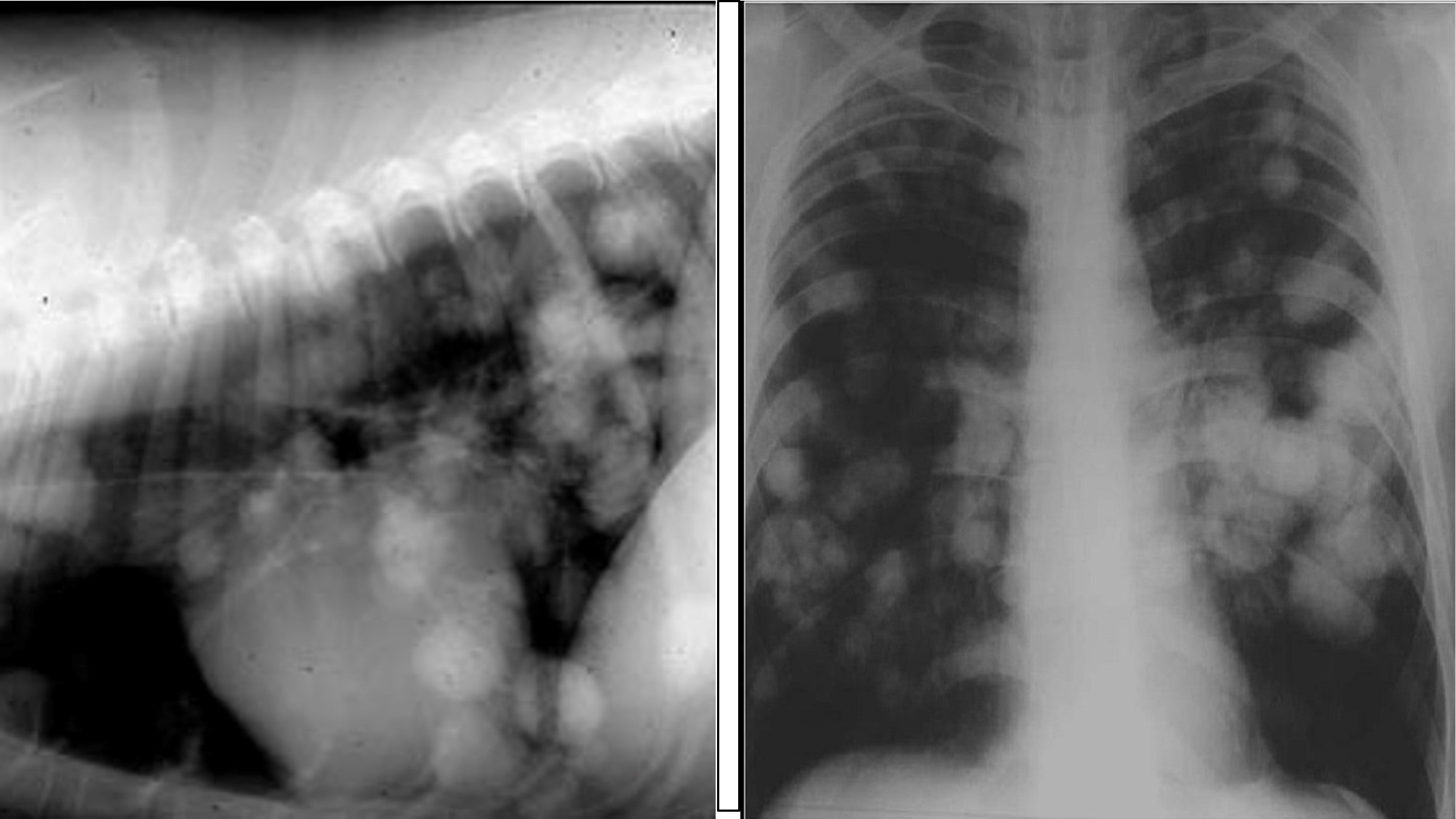

The dog is an ideal large animal model for diagnostic and therapeutic studies and can be used to translate successes to human patients while providing compassionate care to animals and advancing the field of veterinary medicine. Pet dogs share their environment, and oftentimes their diet, with their owners.

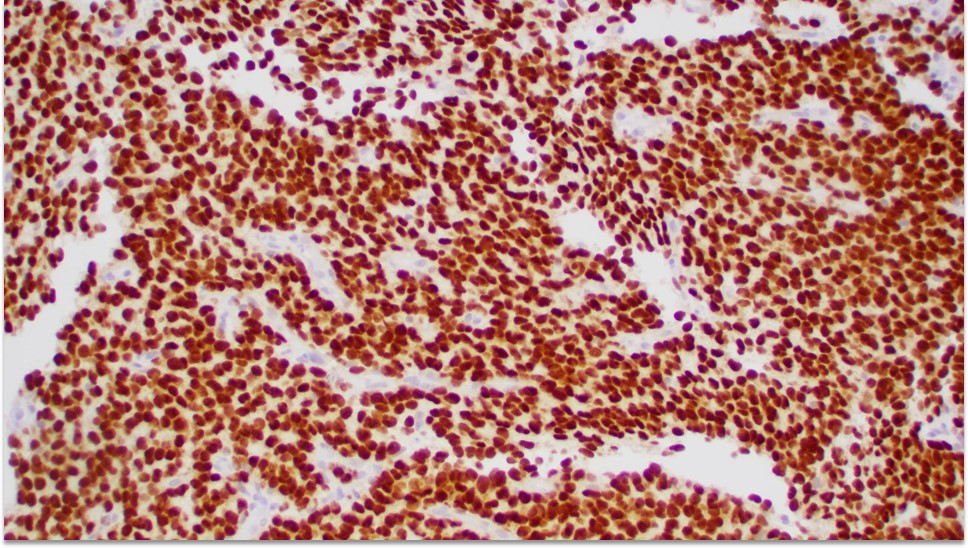

In the field of immunotherapy, dogs offer an innovative model for translational research, as they present many of the challenges faced in scaling up therapeutic systems dependent on complex interactions between multiple cell types yet under more controlled settings.

They also allow for long-term assessment of efficacy and toxicities.

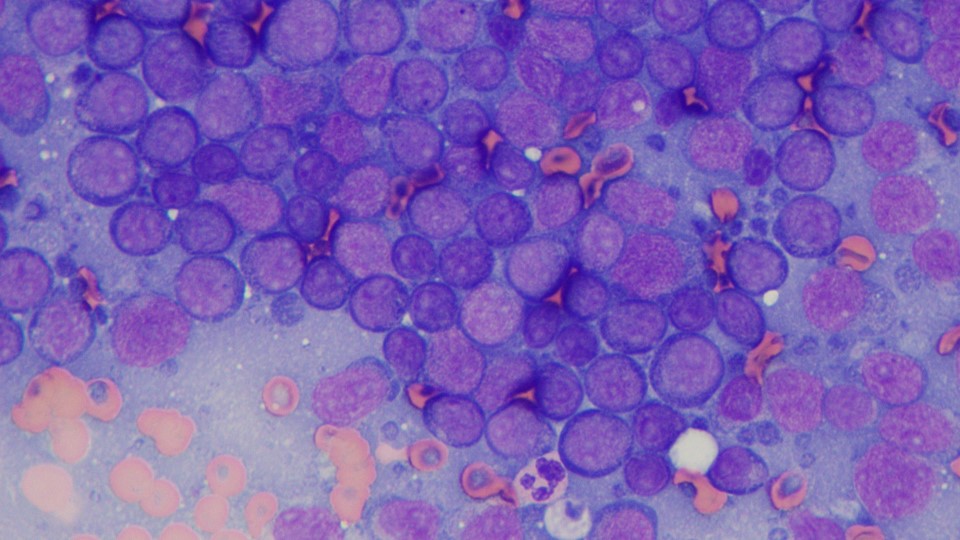

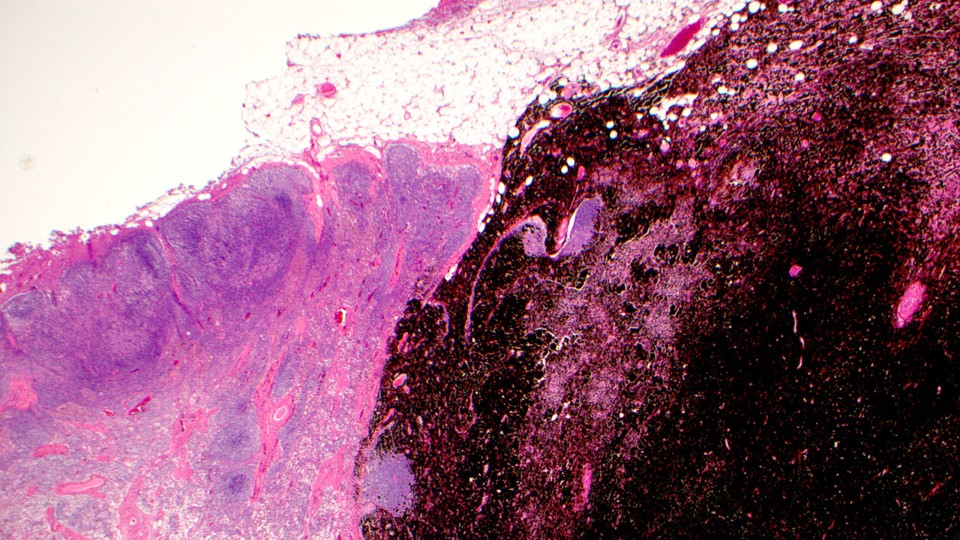

Canine clinical trials offer unique access to a rich source of spontaneously occurring, genetically and immunologically diverse cancers with the benefits of reduced time, expense, and regulatory hurdles of a human trial.

The similarities between canine and human cancers are increasingly being realized. The publicly available canine genome has propelled comparative genomics studies that have shown significant homology between dogs and humans for recognized cancer-associated genes including MET, IGF1R, mTOR, and KIT. Not surprisingly, cytogenetic abnormalities that define human cancers, i.e. BCR-Abl translocations in chronic myelogenous leukemia and RB1 deletions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia have been found in comparable canine cancers.